By Gary Wockner – Save the Zambezi

When we hopped into the safari truck at “Safari Par Excellence” in Livingstone, Zambia, one of our guides handed each of us a “Nyami Nyami” necklace. He had hand-carved the pendent — which is a serpent-like creature — and gave it to us as a good-luck omen for the raft trip.

The fabled Nyami Nyami is a serpent that guards the Zambezi River, and if a whitewater rafter is wearing the necklace, it is said to protect you through the world-famous class V rapids. Tens-of-thousands of tourists, from across the world, come to the Zambezi each year to raft its famous rapids, as well as world-class rafters and kayakers. We laughed aloud as our guide hung the pendants around our necks, although inwardly our apprehension also increased.

It turns out that we passed through the extraordinary rapids safely — thanks mostly to our great guides. But, it’s not really the tourists that need protecting; rather, it’s the river and the rapids themselves which are threatened by a massive hydroelectric dam that would drown and destroy them all.

The Batoka Gorge on the Zambezi River starts a few miles outside of Livingstone and begins just below the thundering cascade of Victoria Falls. The deep, narrow gorge — between 200 feet and 1,000 feet — and the river at the bottom of it straddle the national border between Zambia and Zimbabwe. As you float down the river and navigate the rapids, the guides are often talking and yelling about “Zim side” or “Zam side”, referring to the side of the gorge in either Zimbabwe or Zambia, as they shout about the conditions of rapids, rocks and waterfalls.

We arrived in September, the dry season, which was exceptionally dry in 2019. In fact, it was so dry that Victoria Falls was only half-falling, the entire Zambian side of the falls bone dry.

When rafting the Zambezi, you can make a decision about whether to go in the wet season or dry season. We chose the dry season (which is Fall/Winter in the U.S.) because the famous rapids are a little less dangerous, there’s very few bugs or insects, and the weather is very warm and picture-perfect sunny. Our four-day trip saw almost no clouds, beautiful sunsets, and enough splashes in the huge rapids to keep us cool and smiling all day long.

The “put-in” for Batoka Gorge is literally right below Victoria Falls. We sat on the rocks a little apprehensively as the guides packed up the rafts. The bridge spanning the gorge joining Zambia with Zimbabwe stands right above the put-in and is also a famous spot for bungee jumping. As we waited for the guides to ready the rafts, a bungee jumper came flying off the bridge every 10 minutes, which is just one of the many activities that make Livingstone the “adventure capitol” of Africa.

We traveled in a small group with three guides, one paddle raft, one gear raft, and a safety kayak. The gear raft joined us later downstream instead of traveling through the biggest day of rapids on the first day. As we pulled away from the put-in, the Zambezi’s current pulled us downstream. A few hundred yards later and we hit our first small rapid.

During this dry time of year, the Zambezi’s water is clear and cool, whereas in the wet season, the water turns dark and muddy. The first few rapids are pretty mellow before the famous whitewater begins.

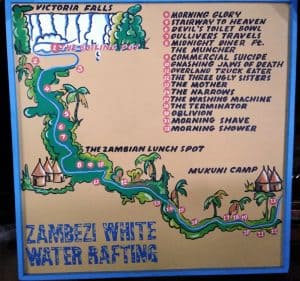

This stretch of the Zambezi is a famed one-day rafting trip that tens-of-thousands of mostly young global tourists take every year. Around eight local rafting companies run trips on the river, the vast majority of those half-day or full-day trips through the raging rapids. Twenty three of the rapids are numbered and named.

Some of the rapids have innocuous names like “Morning Glory”, while others get right to the point with “Commercial Suicide” and “Gnashing Jaws of Death”. Our guide skillfully ran us through them as we paddled feverishly and hung on to the raft. Our general goal was to have fun, get a little wet, but not flip the boat, and our guide carefully granted our request. Through about one-half of the rapids, he simply yelled “GET DOWN!” and we hunkered in the front of the raft and hung on to the “flip line”.

At “Commercial Suicide” (#9) we got out for lunch, and then walked around the rapid. The rapid is considered “Class VI” – not runnable – for commercial trips like ours. On private trips, some rafts and kayaks do get through it, depending on the height of the river. At low water in September, the river carved a deep hole filled with unseen boulders that instantly flipped our raft as the guides let it run down the river empty. The safety kayaker lassoed the raft after the rapid, and after lunch, we climbed back in for more fun.

The afternoon stayed exhilarating as we paddled through “The Mother”, “The Washing Machine”, “The Terminator” and more. At “The Washing Machine” we met other commercial day-trips who were lined up with dozens of rafters waiting to attempt the Class V rapid. We went through first, mostly under “Get Down!” orders, and then watched boat after boat flip behind us with dozens of rafters flying through the air and splashing in the water. Though actually dangerous, all paddlers had helmets, great life jackets, and even better attitudes, and so all we saw on their faces was smiles as the swam by us trying to get back in their boats.

This world-famous day-trip on the Zambezi is also famous on the internet. A quick google and you’ll see numerous videos of huge rapids, boats flipping, and smiling faces all careening down the gorge. In fact, almost every “African expedition” you can book on the internet – with safaris, visiting tribes, and exotic countries — includes an option to raft on the Zambezi River below Victoria Falls.

It’s an absolutely beautiful river, a pristine gorge, and an exhilarating experience, all of which is completely threatened by a massive proposed dam that would drown and destroy the whole thing.

***

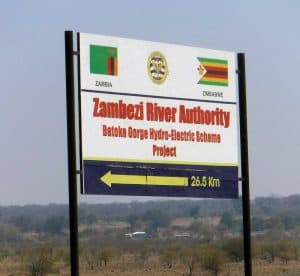

The “Batoka Gorge Dam”, as it’s called, has been proposed for at least seventy years on the Zambezi River. Like all big dam projects in developing countries, this one has been proposed, considered, planned, and then on-again and off-again for decade after decade. An entire book could be written about this proposed dam that included chapters on the relationship between the Zambian and Zimbabwean governments, multi-national engineering and construction firms, financial institutions like the World Bank and Chinese Banks, and on and on.

The “Batoka Gorge Dam”, as it’s called, has been proposed for at least seventy years on the Zambezi River. Like all big dam projects in developing countries, this one has been proposed, considered, planned, and then on-again and off-again for decade after decade. An entire book could be written about this proposed dam that included chapters on the relationship between the Zambian and Zimbabwean governments, multi-national engineering and construction firms, financial institutions like the World Bank and Chinese Banks, and on and on.

All of that changed in 2015 when the World-Bank funded the “Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of the proposed Batoka Gorge Hydro-Electric Scheme on the Zambezi River”, which is exactly like an “Environmental Impact Statement” here in the U.S. (And yes, the World Bank uses the word “scheme”). In June of 2019, the threat-level ramped up significantly higher when General Electric and a Chinese company, “PowerChina”, signed a deal with the Zambian and Zimbabwean government to build the dam. The details of that “deal” are not public, but some actual construction-related work has now occurred — an airport was bulldozed near the dam site, as was a road, both to be used for construction.

The current proposal would be for a 550-foot tall dam that would create a reservoir covering an area of approximately 16 square miles. The reservoir would stretch up and in the narrow gorge to just about ½-mile from the put-in just below Victoria Falls, thereby flooding the entire canyon and completely destroying the whitewater experience. The estimated cost of the project would be around $4 billion and would take 10–13 years to complete.

But it ain’t over yet, as they say.

First, activists and other concerned citizens challenged the “Environmental and Social Impact Assessment” because it was riddled with flaws, and now the World Bank has been tasked with redoing it. At the time of this writing (April 2020), a new draft has just been released, along with proposed public meeting dates, all of which was then postponed because of the coronavirus threat and the need for “social distancing”.

Second, just after my visit in September of 2019, the Zambian government apparently defaulted on payments for the ongoing construction of another dam on the Kafue River, and the Chinese construction company (a different company than proposed for the Batoka Gorge Dam), halted construction and laid off all of the Zambian workers. This raises questions about whether the Zambian government has any ability to pay for the construction of the Batoka Gorge Dam, all of which is cloaked in secrecy because the deal with GE and PowerChina is not public.

Third, the Batoka Gorge Dam still doesn’t make any sense. While the governments in Zambia and Zimbabwe, as well as the media, claim the project is required to bring electricity to rural areas in those countries and to help stop the ‘blackouts’ that are occurring right now in cities, there’s broad speculation that the electricity instead will be sold to neighboring countries for profit. Further, the profiteer may likely be GE and PowerChina, not the African people. Other hydroelectric dams in Zambia and neighboring countries have been built based on promises of rural development, but instead sent electricity to the rapidly growing city of Johannesburg in South Africa and sent money to the dam builders and government bureaucrats.

Finally, there was an extreme drought in South Central Africa in the Fall/Winter of 2019, which means there’s little or no water to operate a hydroelectric dam. In fact, while I was there, Victoria Falls was partly drained dry to run a hydroelectric dam right beside the waterfall, and downstream, the massive Kariba Dam was operating at very low capacity. If there’s not enough water in the river right now to spin the turbines already in place, adding more dams and turbines likely won’t generate much more electricity. Further, while I was there, the Zambian President was on the front page of “The Daily Mail,” which is the national newspaper, saying “Nuclear science is the answer for drought”. Even further yet, everyone I talked to thought solar power made the most sense — the sun is out all the time in the dry season, and about ½ of the daytime in the wet season.

Like all things related to dams and other large, expensive construction projects – especially in developing countries – what makes sense and what actually happens might be world’s apart.

***

Camping in the Batoka Gorge is spectacular, especially in the dry season and especially near the end of the rafting season with few tourists around. The tourists that do the day-trip miss out on some of the longer, quiet stretches of the river and the gorge, as well as the biggest rapids and best landscapes of all.

A stretch of the river called “The Narrows” is a slotted-rock crevasse ten to thirty feet high and sometimes only twenty feet wide with the deep swift river racing through it. In sections where the river flattened out, we saw small crocodiles basking in the sun and heard stories of even larger crocodiles that occasionally chased after kayakers. The farther downstream we went, the higher the gorge walls became, increasingly canyon-like. Farther downstream, Upper Moemba Falls is beautiful and raftable, a picture-perfect scene. Lower Moemba Falls is a raging thirty-foot drop that we spent two hours portaging around.

The evenings were clear and cool, the food and drink was excellent, and the tranquility seemed a world apart from the bustling tourist hub of Livingstone. At night, we had a full moon which cast its eerie light across the canyon, but before the moon came out we saw vast reaches of stars including the Southern Cross. All the while, we wore the cross-like Nyami Nyami necklaces to keep us safe.

The “Nyami Nyami” has more to its story than just as a protector of rafters on the river. Legend has it that the Nyami Nyami is the powerful male serpent that lives in the river, but his female partner is trapped behind the giant Kariba Dam downstream on the Zambezi. While the Kariba dam was being built, the local tribe — the “Ba-Tonga” people — told stories of the male serpent’s anger at being walled away from his wife, after which the male serpent created massive floods in the river that destroyed the first attempts at building the Kariba Dam.

The take-out for the four-day rafting trip is right at the proposed dam site. After we unpacked the gear, we hiked up the steep cliff for an hour to get to top of the canyon. I only saw beauty and wildness on this day as I peered across the canyon and down at the river, but I pictured a vast wall of cement with a massive angry serpent lashing up against it.

Read the original article here.

***

Gary Wockner, PhD, is an environmental activist and writer based in Colorado who travels widely protecting rivers across the planet. He works with the global Waterkeeper Alliance which has launched a “Save The Zambezi Waterkeeper Affiliate” helping to protect the Zambezi River.

Join the fight to Save the Zambezi:

Facebook @SaveTheZambezi